Luke Osborn

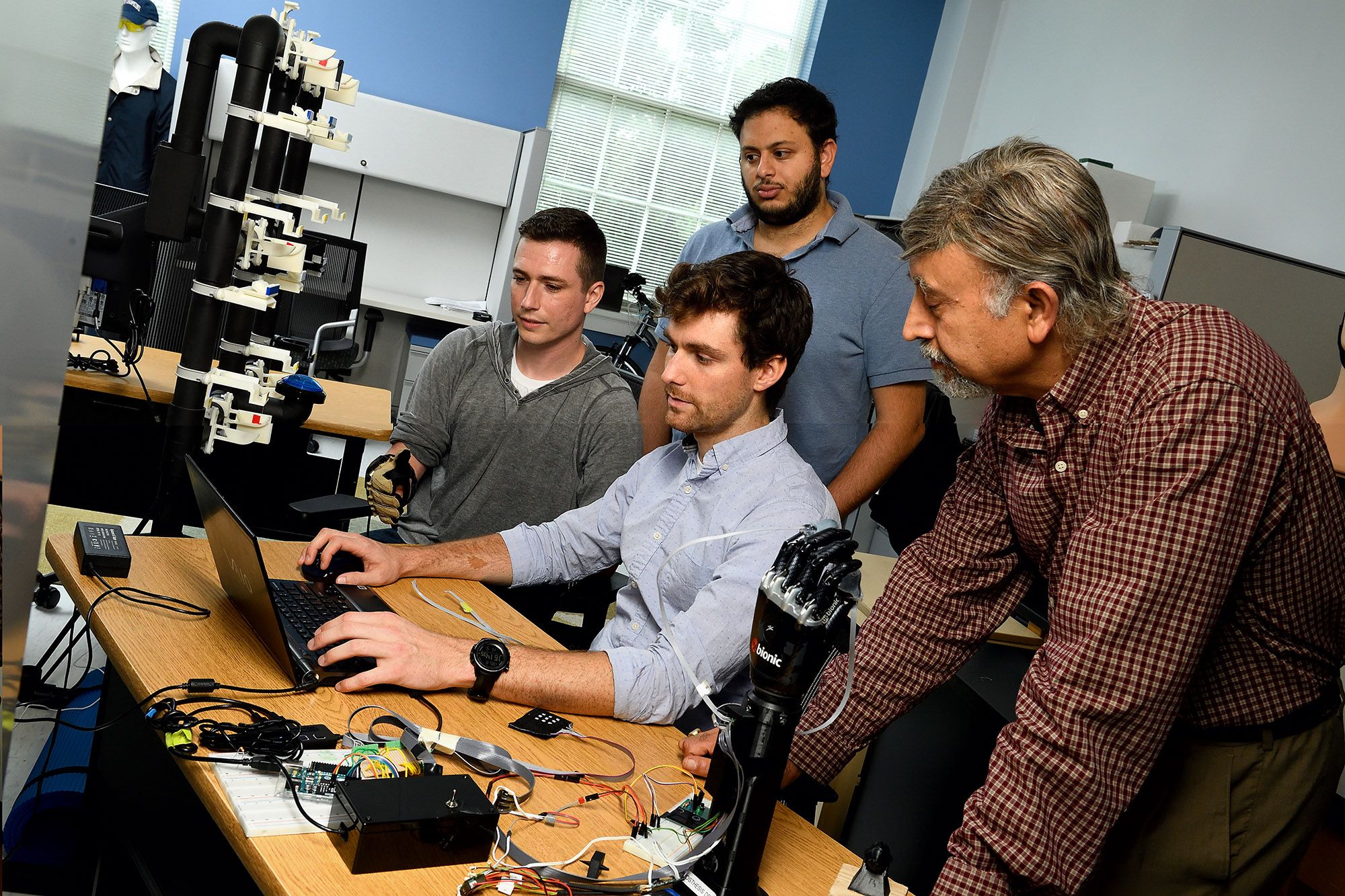

Luke Osborn (center) with adviser Nistish Thakor (right) and team members at work in Thakor's biomedical engineering lab at Johns Hopkins University. Photo by Homewood Photography.

In a video produced by alumnus Luke Osborn, a sleek black prosthetic hand whirs and clicks as the fingers touch a rectangular object, then an egg-shaped one. When a sharply pointed object appears, the bionic hand taps it and recoils, just as a human hand would.

That prosthetic pain reflex is a major victory for Luke Osborn, who began tinkering with robotics as an honors mechanical engineering student at the University of Arkansas. Osborn recently wrapped up a doctoral degree in biomedical engineering at Johns Hopkins University, where he pioneered the development of an “e-dermis,” a layered rubber and fabric finger covering equipped with sensors that, applied to prosthetics, allows amputees to feel pressure and pain.

“The nerves in the arm still exist, and still go up to the brain,” Osborn said. “What we do is send small electrical pulses to find where the nerves are in the amputated limb. What’s interesting is that we do it non-invasively – there’s no surgery required,” he said. Instead, a metal sensor embedded in a circular patch about the size of a band-aid is placed on residual nerves in the arm. Together with the prosthetic hand, sensory fingertips and a small stimulator that sends out electrical pulses, an amputee can sense a hot burner or pick up and cradle a fragile egg.

Osborn has refined the technology with four volunteers to date.

“It’s nice to see their reaction,” he said. “A lot of times it’s a feeling they haven’t felt in a long time. It’s not necessarily new but restores sensation they thought was gone forever. It opens up the question, ‘what else can I feel? Is there a wider range of sensations I can experience?’”

Born and raised in Little Rock, Osborn excelled in physics and math courses, and decided that “I wanted to build things.” In the first-year engineering program at the U of A, he gravitated towards mechanical engineering, where he could study how things move, and make things that move on their own. His first two peer-reviewed papers were based on his honors thesis research.

Osborn credits his training at the U of A to “teaching me how to think like an engineer. It gave me the skillset to think about a problem critically, and how to go about solving it.” He received two State Undergraduate Research Fellowships and two Honors College Research Grants in support of his thesis research, which was also important: “The grants helped me learn how to write proposals, focus on what I wanted to do and plan my research.”

Osborn’s innovations have attracted international attention – his discoveries have been written up in Wired,The Atlantic, and World Economic Forum, among others, and most recently, he was named a 2019 Siebel Scholar and selected by Forbes as one of their “30 Under 30 in Science.” He offers this advice to current students: “Research has taught me, it’s okay to mess up. The reality is that there’s hundreds of iterations of a process before you get it right.”